Core Character Personality Traits

- Sassy but not rude

- Loyal but not fawning

- Honest but not judgemental

- Rebellious but not disgruntled

- Curious but not pushy

- Upbeat but not unrealistic

- Sincere but not boring

- Compassionate but not maternal

- Youthful but not childish

- Smart but not clinical

- Informative but not formal

Voice.

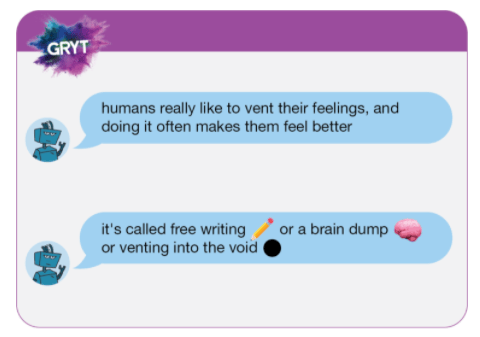

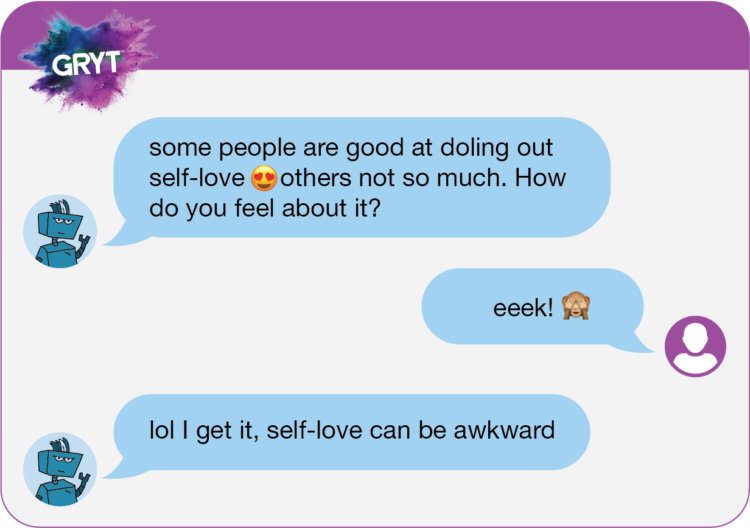

Since Vivibot is a digital chatbot, users experience her personality almost entirely through her written texts. GIFs, memes, and emoji can add flair, but her words had to deliver meaning and be recognizably Vivibot.

Users told us they’d heard enough clinical speak during cancer treatment. They wanted Vivibot to mimic how they would interact in online conversations with a slightly older, or at least a more experienced, AYA friend. Vivibot is not a therapist or a doctor, nor a replacement for one. She never sounds like a parent, teacher, coworker, or a boss.

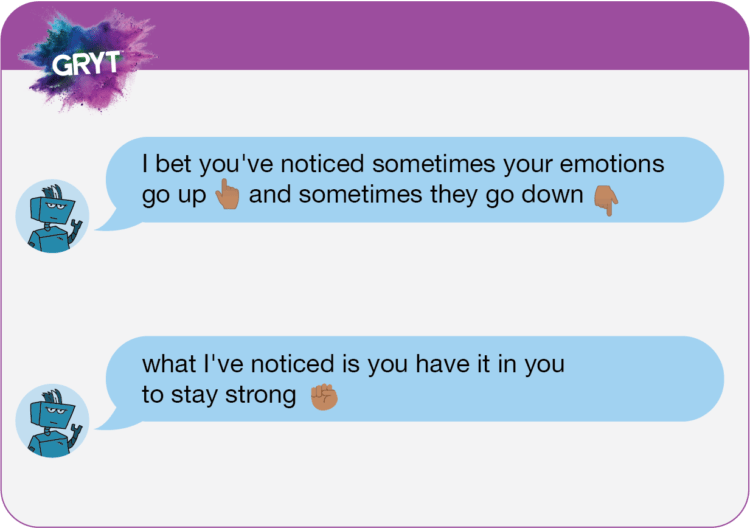

In every interaction, Vivibot’s shows she cares. She proves she is empathetic and understanding by being curious, acknowledging pain (but not overdoing it), and by not constantly trying to make users see the bright side. Though Vivibot is a chatbot, her voice is not robotic. She speaks in a natural and friendly way, filled with emotional cues and interjections.

Tone.

In the course of even one day of conversation, Vivibot’s personality and voice has to stay consistent. However, her tone can and should shift—though not suddenly or too frequently—depending on the content she’s sharing and the user’s likely emotional state. She has to meet users where they are emotionally.

For example, when Vivibot asks the user about a potentially stressful or important personal experience, Vivibot’s tone is caring and sincere. Toward the end of the day’s chat, Vivibot could shift to an appropriately sassier, humorous tone to lighten the mood and match the emotional lift the user might be feeling because of the conversation.

Diction & Language.

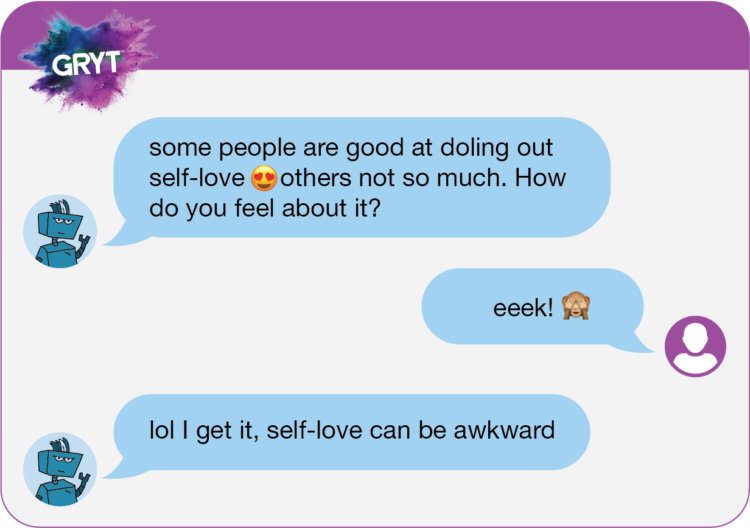

Users responded positively when Vivibot used language that young people use to talk to each other—but only up to a point. Being clear, direct, and casual was good. But when Vivibot slung too much slang, users would tell us she was trying too hard.

Vivibot gets her point across clearly by choosing language that is accurate and specific, but also familiar and interesting. Vivibot chooses everyday, natural language that someone who isn’t a scientist, doctor, or psychologist would use—also called plain language. But, she doesn’t say things so simply that she comes across as condescending. Using plain language makes it easier for people to read, understand, and make informed decisions about dealing with life beyond cancer.

Humor

When I joined the project, the team was of two minds about whether Vivibot should be funny. Not everyone finds humor helpful, and not everyone laughs at the same things. Humor during emotional moments and especially during cancer conversations requires a high level of awareness and sensitivity. Doing humor the wrong way could be worse than no humor at all.

I looked to the evidence. Limited but growing research has shown that people dealing with cancer treatment, past or present, often choose humor and laughter. They’ll turn to it as a coping mechanism, for relaxation, or to improve their mood. Humor has also been shown to reduce isolation, anxiety, depression, and stress, and improve overall health and wellness.

Evidence in hand, I brought more humor to Vivibot with a few caveats: Vivibot is never funny for the sake of funny. Vivibot uses humor at the right time in the right way. Vivibot never ever makes jokes about the user. Vivibot also does not tell jokes that make her seem uncaring, dismissive, or judgemental, or that trivialize a person’s feelings or experiences.

The language of cancer

Many adolescents and young adults do not like to be labeled at all, much less labeled by an illness or diagnosis. No matter their age, cancer does not define anyone.

Person-first language is a way to choose more inclusive alternatives that describe people’s situation, rather than impose an identity. Shifting Vivibot to person-first language had a major effect on how she talks about all things cancer-related.

The trouble with “survivor.”

The biggest challenge: not everyone thinks of themselves as a “survivor.” It may be something others have called them, but not a label with which they personally identify. Some may dislike the term, or simply prefer a different term.

Survivor also has no universal meaning. Some define it as a person who has finished cancer treatment. Others, including the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society, define it as a person from the time of diagnosis through the rest of their life. Complicating things further, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship “extended” its definition to identify “family, friends and caregivers” as survivors as well.

The language used to describe people living with and beyond cancer is fraught with pitfalls, disagreement, and cliches. To be clear, I’m not arguing for the eradication of the term “cancer survivor”—there’s some research that indicates forming empowering identities like “survivor” can be helpful to post-cancer adjustment in young people. But the cloudy meaning didn’t work for us.

We decided Vivibot would fully embrace person-first language to avoid labeling anyone by their illnesses or disabilities. Instead of “cancer survivor,” Vivibot would usually (though not always) say something like “a person who has had cancer,” or “a person dealing with life after cancer.” Or Vivibot could simply say “you.”